The Richard Wagner Society of the Upper Midwest

The Richard Wagner Society of the Upper Midwest

Our History

by David W. Cline, M.D.

Wagnerian Influences in the Upper Midwest

A New-World Bayreuth?

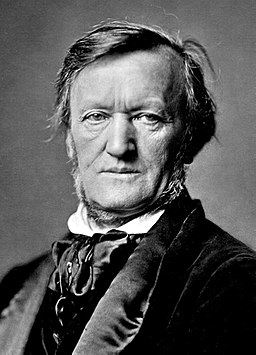

Avid interest in the music dramas and philosophy of Richard Wagner in the upper midwest goes back to the 1870s. During that period, several St. Paul, Minnesota businessmen corresponded with Wagner, inviting him to come to the midwest and promising to raise a million dollars to build a Festspielhaus to his specifications on the banks of the Mississippi River and to support him financially thereafter. The deal was brokered through Newell Fill Jenkins, an American dentist practicing in Dresden, who treated Wagner in Basle and Bayreuth on several occasions and was entrusted with the negotiations involved in Wagner's proposed immigration to American in 1880.

Wagner's interests in coming to Minnesota appear to be financial, philosophical and sociological. He needed considerable amounts of money to build the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth and mount the first production of "Der Ring des Nibelungen," all of which finally occurred in August 1876. Even though the festival was a success -- Frederic Spotts says, "Every one who attended agreed...the festival was just not the cultural event of the century, it was one of the great moments in cultural history," -- it was not a financial success. Although King Ludwig II of Bavaria supported the enterprise, Wagner hoped that Bismarck, Chancellor of the newly formed German nation in 1971, would give financial support and adapt the festival as a symbol of German art, an "artistic sister of German unification, "with Bayreuth to be "a sort of Art-Washington D.C." However, no financial support was forthcoming. The Iron Chancellor Bismarck, who could not abide Wagner, was not enticed by the offer and made sure that Wagner's project received no financial support from the Reich nor did he attend the first festival. Wagner thus realized he had failed to make the Bayreuth festival a theatrical symbol of the national consciousness and ascendant military power of the new Germany.

Wagner responded to this affront with a growing disillusionment with the Fatherland and contemplated immigrating to Minnesota, whose German-American citizens had offered to subsidize a new world Festspielhaus. He delighted in the idea of founding a "new society" in the new world with a theater, school and home in Minnesota where, in Wagner's opinion, the best Germans had immigrated - preserving purity in racial stock - while the Old Germany and the rest of Europe, sank into decay. Wagner even set about educating his son, Siegfried, for a future as an American. Dr. Jenkins attempted to cool this ardor, persuading Wagner that the United States would certainly welcome the great composer, but the religious attitude toward Wagner's music dramas that Wagner demanded, which had not developed in Germany, was even less likely to take hold in the United States. So, this idea treasured by Wagner in his later years, came and went. David Large, in the Wagner compendium, edited by Barry Millington says, "It is a shame he did not make this move: A new world Bayreuth in the American middle west would certainly have had a more wholesome influence on the evolution of Wagner's legacy."

Owatonna, Minnesota

A Wagner legacy of a different sort did appear in Minnesota. It took the form of architectural design of a bank in southern Minnesota build in 1906. The National Farmer's Bank of Owatonna was designed by Lewis Sullivan, an architect from Chicago. Sullivan was swept away by hearing Wagner's concerts in Chicago "revealing anew, refreshing as dawn, the enormous power of man to build, as a mirage, the fabric of his dreams." John Root, another older Chicago architect, gave theoretical shape to this vision in his treatise, "The Art of Pure Color" in 1883. Root added an emotionally effective and symbolic function for color that was explicitly derived from an analogy with Wagner's music. Lewis Sullivan in his architectural masterpiece in Owatonna used abstract color and architectural ornament to create a "color tone poem" or "a color symphony," as he called it, designed to evoke emotion and the appearance of the natural world in this Prairie School large cubical with skylight and stained glass windows. Larry Millet describes the color phenomena as follows:

"The ultimate mediator of color in the banking room is the natural light that pours through the huge semicircular windows and the skylight above. Filtered by these great expanses of stained glass, the light as it enters the banking room has peculiar and strikingly beautiful quality likening it to 'sunlight passing through sea water.' The quiet blue-green glow created by this interaction of sunlight and colored glass gives the room an ethereal aura not usually associated with the down-to-earth business of banking which is so dominant that colors in the bank are never quite what they seem. Thus, ornament on the upper wall that appears green turns out to be blue when viewed in more neutral light. The light also changes with the movement of the sun across the sky, with weather conditions, and with the time of year. As a result, the ornament that fills the bank goes through subtle shifts in color from hour to hour, day to day, and season to season. By bringing indoors and outdoors together in the banking room through the manipulation of light, Sullivan was thus able to compose his 'color symphony'-- a symphony conducted by the sun itself."

Thus, architecture becomes the best of the visual arts to realize Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk--the total work of art.

Red Wing, Minnesota

Owatonna is not the only Minnesota community that pays homage to Wagner. The Sheldon Theater in Red Wing was built in 1906. On the outside of the building at the upper level, there are several coves wherein stone busts of famous people of the theater can be placed. On one cove sits the bust of William Shakespeare, at another the bust of Richard Wagner. Many coves remain empty. It is remarkable that the people of Red Wing knew and admired Wagner to the point of memorializing him in this way. Probably there are other stories to tell in this same vein -- unheard but solicited by this writer.

The Richard Wagner Society of the Upper Midwest

Since history has the greatest impact when it has personal meaning, we who are interested in the music, musicology, and philosophy of Richard Wagner, must ask ourselves: What has been our personal experience with this work? How did we become interested and what fascinates us? What brings forth passion? These time-honored questions have been the basis for the newly revived Richard Wagner Society of the Upper Midwest, one of 120 such societies throughout the world. Upon entering this society, each new member is asked, "How did you become interested in Wagner's music dramas?"

My answer began when I was 19, in 1954, on a visit to New York City and particularly Louchows German-American restaurant, where on the upper interior walls were dramatic murals that caught my attention. Because I did not understand them, I asked a waiter who briskly said, "What! You don't know what stories they tell? They are from Wagner's operas!" Then he glared at me and said, "Those operas started two world wars and they will start a third!!" That music dramas could start world wars was astounding to me, coming as it did shortly after World War II. I determined that day to try to understand the veracity of his pronouncement; I am still learning.

The Society as we know it today first met on July 22, 1998, at the Minneapolis Club with four people in attendance. The conversation centered around the questions listed above. We continued to meet about four times per year and usually discussed recent experiences with Wagner's music dramas: The Flag Staff Arizona "Ring" in June of 1998, "Lohengrin" at the Metropolitan Opera, NYC October 1998, the San Francisco "Ring" in June 1999, "Tristan" and the Wagner Symposium in Honolulu in February 2000, the Metropolitan Opera "Ring" in spring of 2000, the Seattle "Ring" in August 2001, the Bayreuth Wagner Festival August 1999, 2000, 2001 and the Wagner Festig in Berlin spring of 2002.

On one occasion, November 11, 2000, we had an outside speaker. Penelope Turing from London, who had attended all but one of the Bayreuth Festivals since their resumption after World War II in 1951, spoke about her experience and the changes she had noted: "Fifty years of Bayreuth Festivals with Wolfgang Wagner."

Other meeting topics include "What Virginia Wolf had to say after attending the Bayreuth Festival" and the concept of "Wahn" in Wagner's music dramas. Elinor Watson Bell presented her experience studying music and attending Wagner operas in Munich in the early 1930s, complete with her scrapbook of program performances and performers.

Our general goal is captured in the motto of the Wagner Society of New York: "To learn, to teach, to share appreciation of the musical works of Richard Wagner." Those of like mind are invited to join.

References

Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. Frederic Spotts, Yale University Press, 1994, p.78

The Curves of the Arch: The Story of Lewis Sullivan's Owatonna Bank, Larry Millett, MHS Press, p.88

Richard Wagner: The Man, his Mind, and his Music. Robert W. Gutman, Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc. p.404-405

The Wagner Compendium, Barry Millington, General Editor, Thames and Hudson, 1992, p.390,401.